Bonner Kunstverein

Bonn

Lucie Stahl

Seven Sisters

Mar 12, 2022

Jul 31, 2022

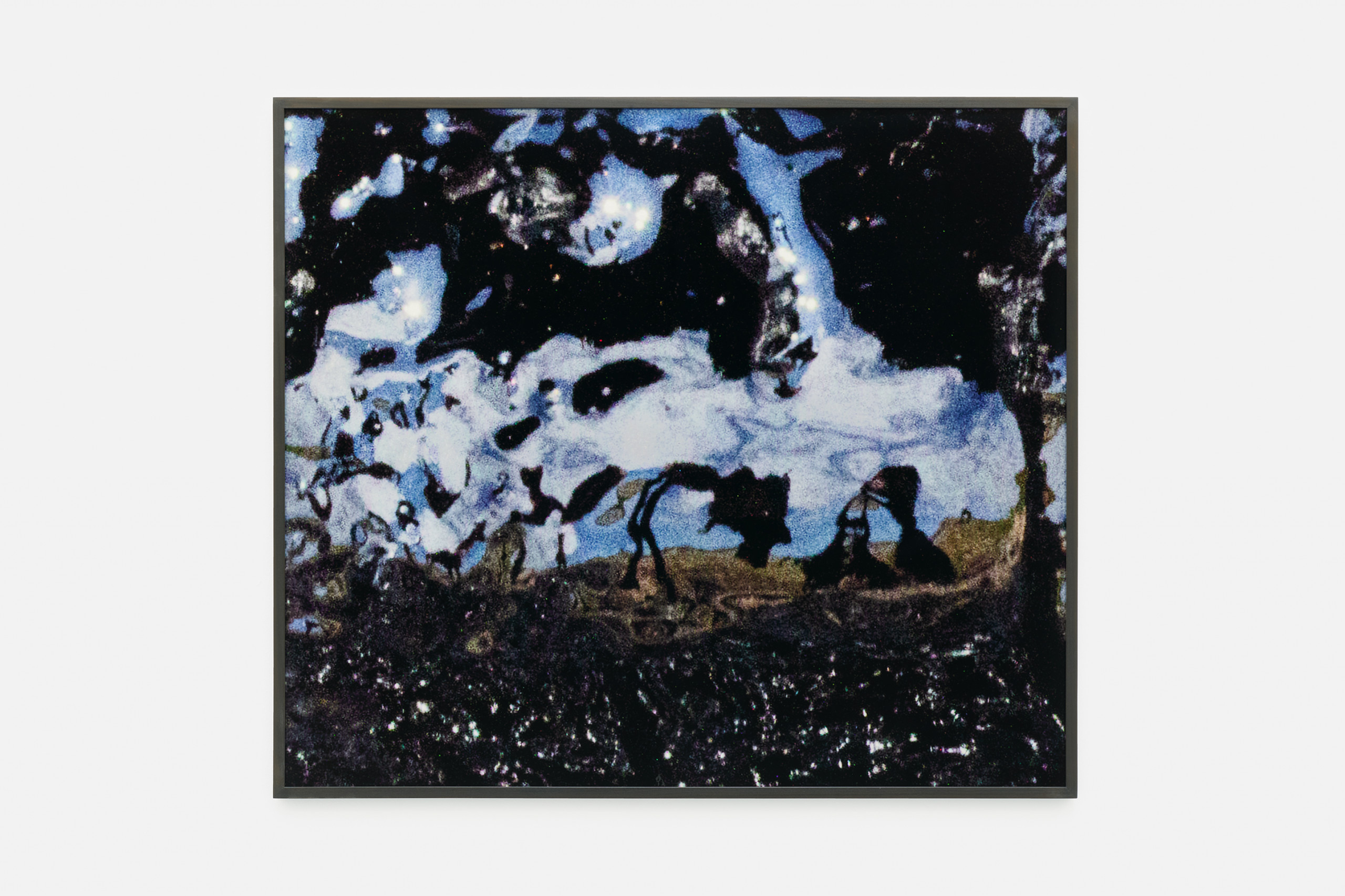

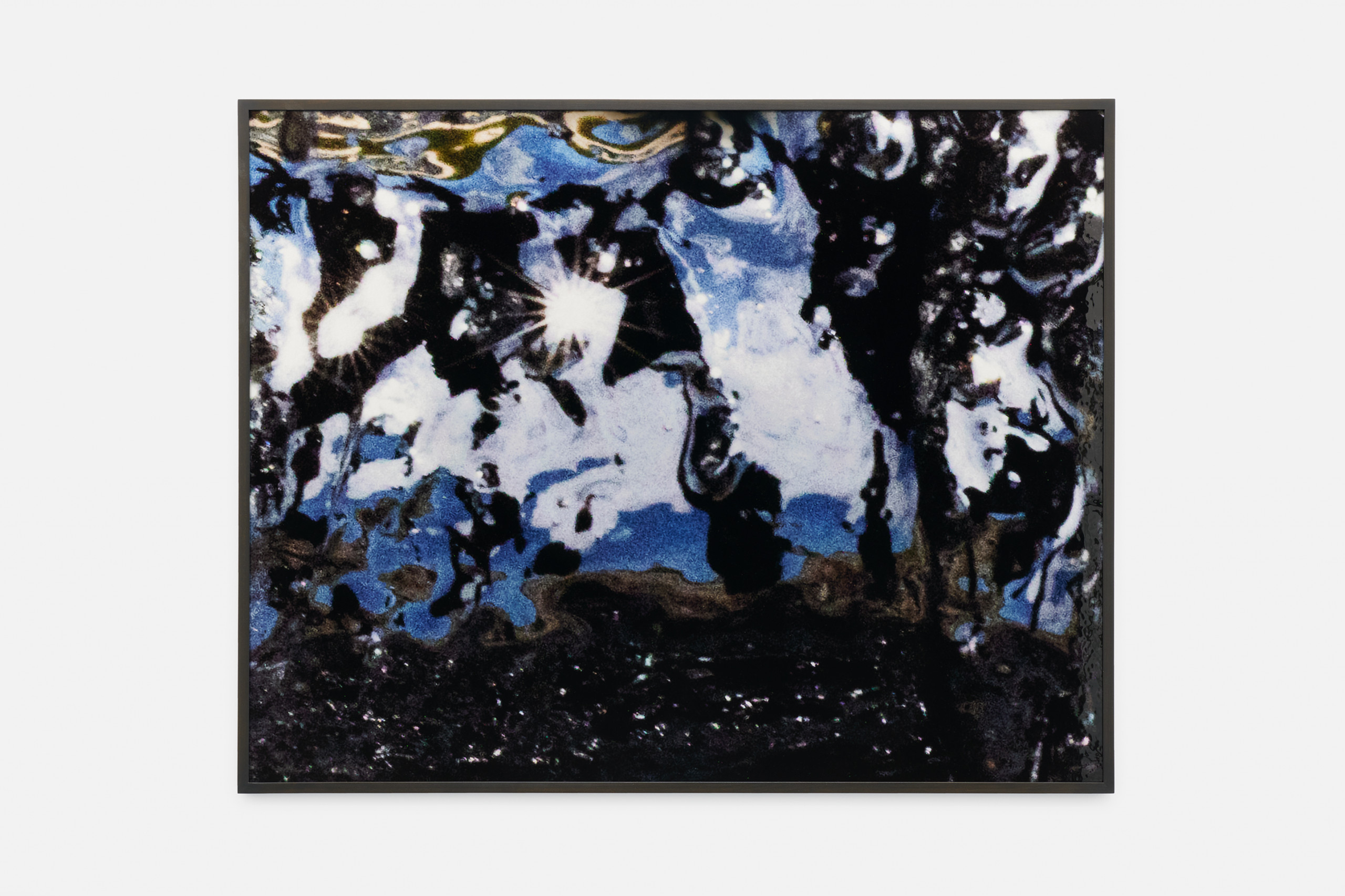

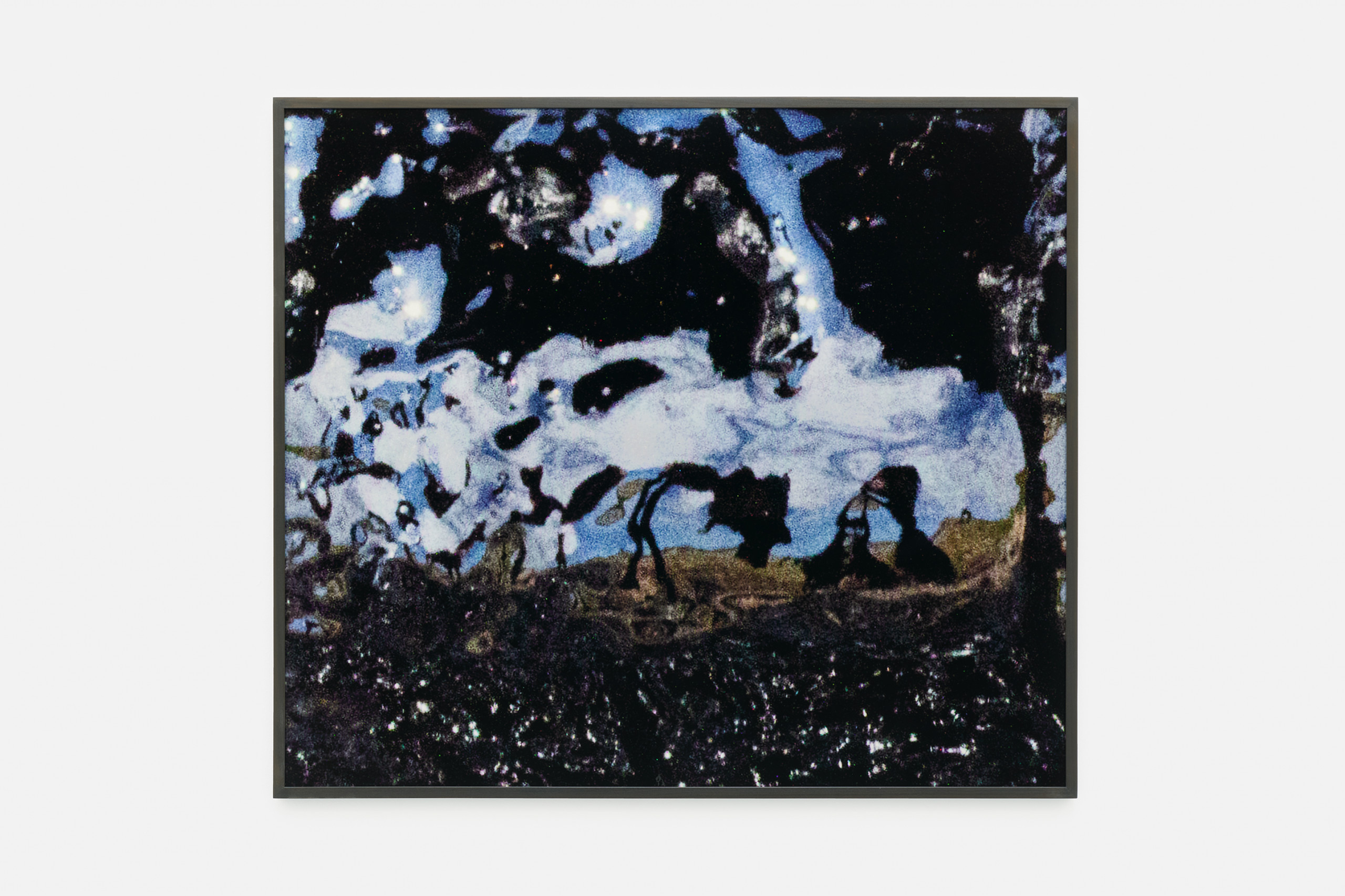

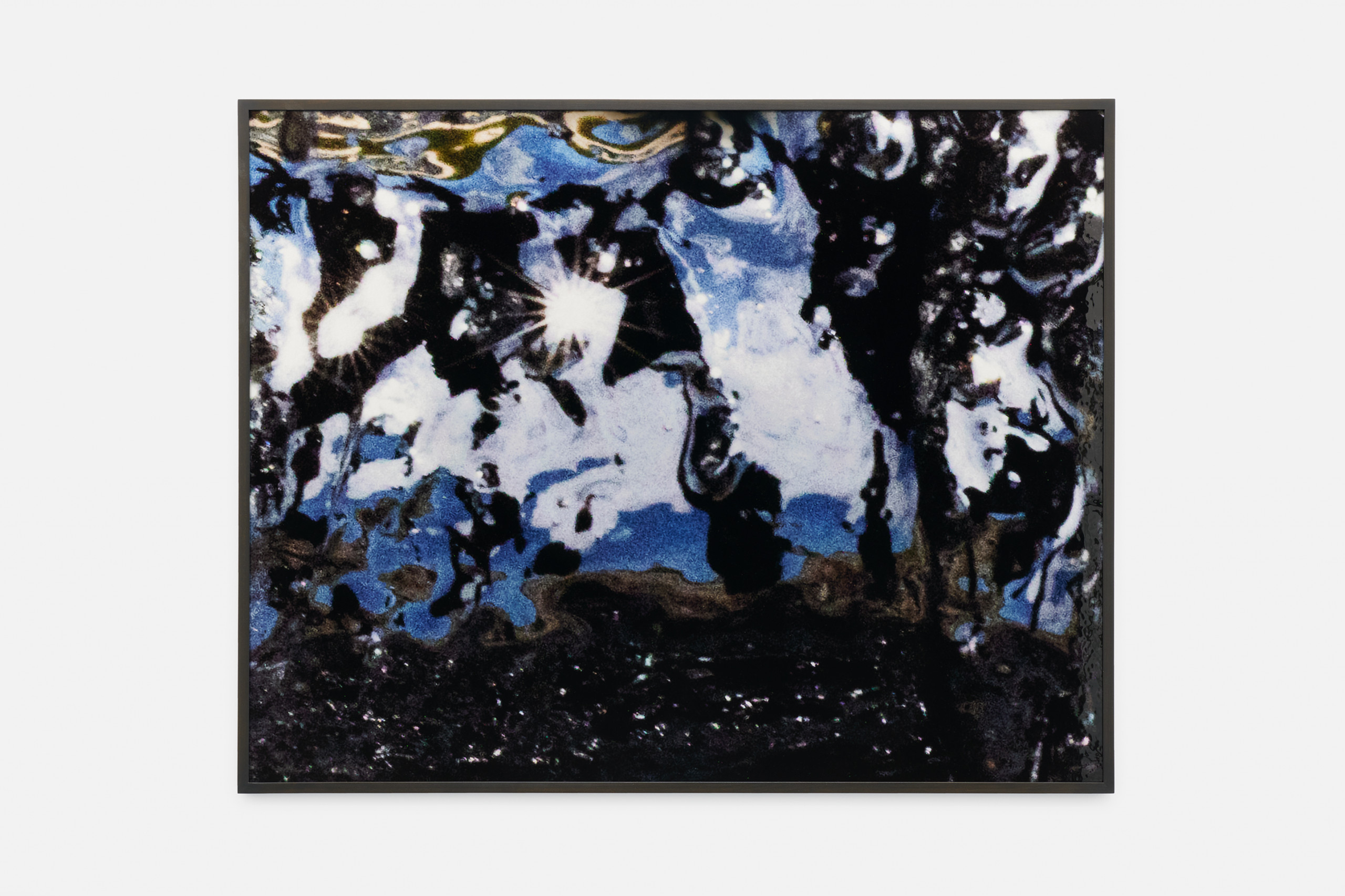

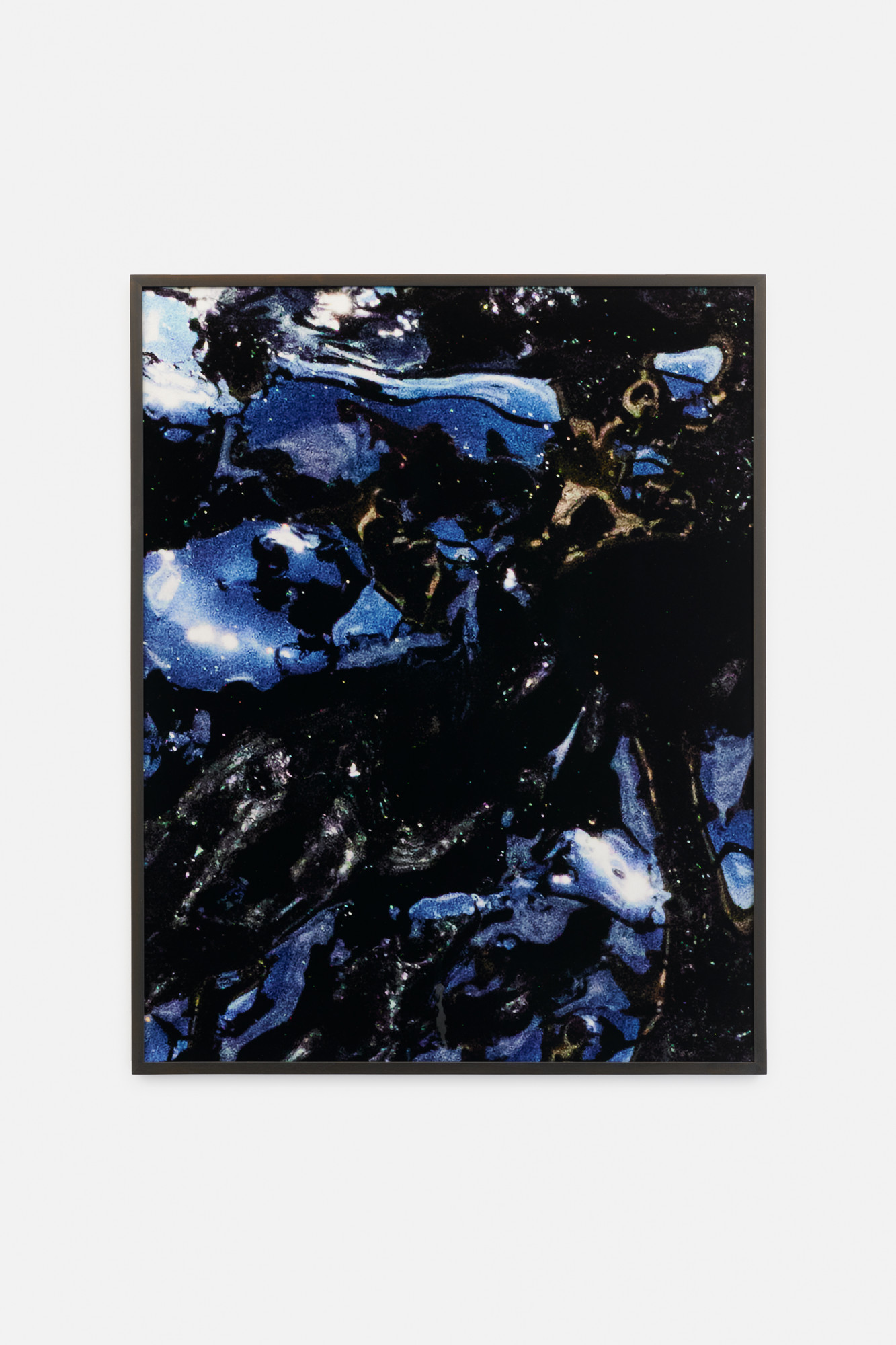

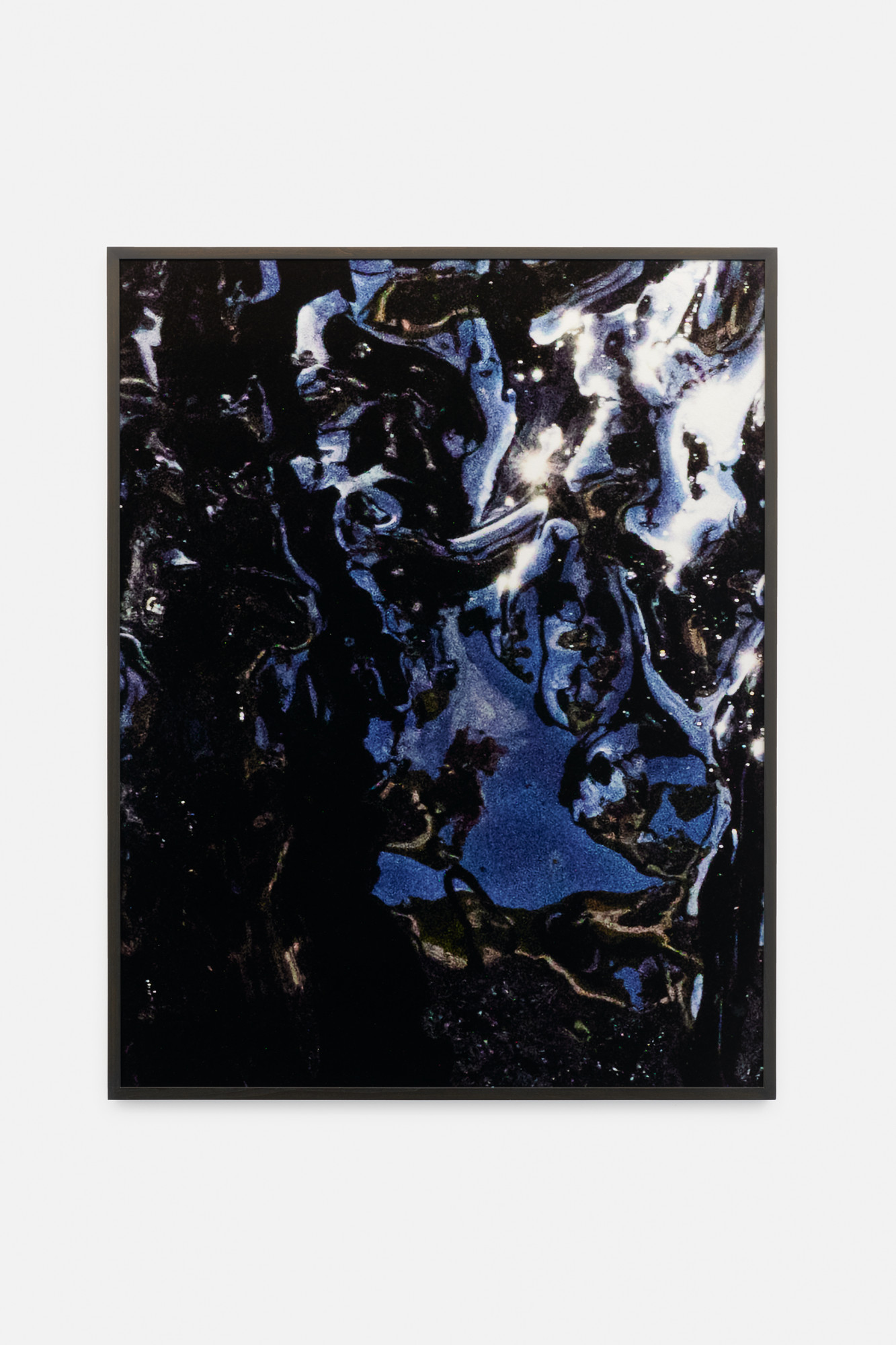

There are structural parallels between the fossil fuel and dairy industries. Both involve sucking, pumping, flow and pressure in the extraction of a raw material to be repurposed for growth and energy. There are also largely neutralised ways of seeing and relating to other beings and the earth that are at the core of these modes of production and consumption. Such links and slippages materialise in Lucie Stahl’s work. Her visual language is ambivalent yet exact, playing off the collective sense that the shifting ground of daily reality may be a warning of imminent systemic collapse. In Seven Sisters, there is a continuous process of moving close to, and abstracting. In approaching a field that is almost too big for words, she zooms in on the details in lieu of attempting an impossible overview. In a suite of newly conceived photographic works, a series of crude oil close-ups from an abandoned oil field are captured, the materiality and the seeping or bleeding nature of their openings brought onto a silvery plate. The substance, a remnant of a prehistoric natural world, combined with the materiality of the photographic sheen create both surface and unknowable depth. In the puddles, creatures and forms offer themselves up to us: one might see two beings trailing through a storm; a monstrous profile emerging from the sea, and then the half-submerged outlines of an animal trapped in the actual puddle. These spots of ‘waste‘ are surreal in the close viewing – a sense of strangeness and unreality which seems to touch something at the core of our submerged/subconscious relation with cycles of consumption and waste.

The work is in dialogue with select earlier pieces of Stahl, such as Giants, a series of somber photographic views of oil platforms. The epically massive machinery stands in water like stoic automatons, the depths of their foundation and drills extending beneath water and below that, hundreds of meters underneath the surface of the earth. What we view here is the tip. In the unseen, the Giants are moving through the seabed, extracting as part of a cycle ecologist and activist Andreas Malm has described as the ‘warming condition’. The terrifying scale and impressive brutality of these complexes also articulate the depth of what cannot be seen, or that which might only have been half-acknowledged. Yet, as soon as the vertigo-inducing possibility of darkness and monstrosity emerges in Stahl’s work, there is also the possibility of the counter, through ambivalence, through destabilising lightness and humour. This is the case of FUEL, an oversized creature on four legs, reminiscent of a milking machine. There is a cartoonish quality to this beast, its thin legs resting on its suction feet. The scale is absurd, a zooming-in effect on the metallic joints and limbs, including the suction openings devised to hold on to soft tissue.

A key strand of the exhibition is drawing on these long-running concerns but also leaning into new spaces of materiality and mood, a quality most powerfully sensed in the new sculptural installation Seven Sisters. The title alludes to the eponymous conglomerate of seven transnational oil companies that dominated the petroleum industry after the Second World War, the sisters referencing the mythological Pleiades fathered by the Titan Atlas. Taking the form of steel towers, reminiscent of deep sea oil rigs and drilling pumps, they breathe the optimism of an early industrial, new frontier idea of nature’s bounty. The figures, like fine line-drawings, each exude their individual character stance and attitude, and a sense of embodiment all the more strange through their skirts and ribbons. There is a restricted quality to these creatures, tied together, held in a grip teetering on the edge between the erotic and force. An undertone of bondage complicated by the logic of the milk and oil extraction within which they assemble.

The architecture of the exhibition has been conceived with an unfolding quality, interconnected chapters and moments of concentration, where inside and outside seep into each other. As such, the show begins and ends with a work extending out into the outside, and the front yard of the Bonner Kunstverein. Drawing on the shape of Tibetan prayer wheels, the sculpture takes the form of a metal frame, holding a line of oil cans, for users to spin and turn. An allusion to the sublime or transcendence, being at once still that, and also, simultaneously a tactile encounter with exuberance and exhaustion.