Fitzpatrick Gallery

Paris

Louis Eisner

Leaving Cheyenne

Jun 08, 2022

Jul 23, 2022

A mythology of insanities; a capricious faun, a house in the middle of a forest, a woman with the head of a donkey, slag pots and statuary monkeys, in-between anxious landscapes, constitute a disguised horror play. Flirting with the languages of fatality, this post-industrial plot envisions the last appearance of a doomed prediction. Patiently waiting for the blast, nothing remains crucial: the characters take their roles in the middle of a collapse. With no matter of commotion, what remains? At last, a compulsive obsce- nity pushing towards climax with vacuity.

Driven by personalities inherently conflicted by lunatic tendencies, Louis Eisner’s Leaving Cheyenne opens and closes on a static questioning: isn’t the devil among us? Posing this question as a crucial part of a current environment of fear, displacement, and dizziness.

Read the conversation: Hugo Bausch Belbachir in conversation with Louis Eisner

Louis Eisner (b. 1988, Los Angeles) lives and works in New York City. He studied Art History at Columbia University.

Recent solo exhibitions include: Slag Pots, Manual Arts, Los Angeles (2022); Where Seldom is Heard and The Journal, New York (2021)

His work has been included in group exhibitions at: PAENA @ PRAXIS, Mexico City (2022); Fitzpatrick Gallery, Paris (2021); Blum & Poe (Los Angeles); Almine Rech, New York (2018), Galeria La Esperanza, Mexico City (2016); Zablu- dowicz Collection, London (2015); Fondazione Museo Pino Pascali (2014), et. al. He was a founding member of the artist-run organization Still House Group from 2010 to 2016.

PRESS

Contemporary Art Library

Everything in-between

Louis Eisner in conversation with Hugo Bausch Belbachir

Hugo Bausch Belbachir : When we met last time I introduced your work saying that it has been focused on investigating the ideologies of representation through recurrent symbols; storm drains, slag pots, windows, buildings, desert landscapes, ships - often elaborating a panorama on anger, fear and dizziness within city and rural environments.

Louis Eisner : Symbols is a good word, but I like characters more, especially when referring to animation when the symbols become alive; a house that would start to talk or a door that sneezes.

H.B.B : Figures.

L.E : Anthropomorphized figures, yes, who have features we can identify with. A slag pot has a face, and I can see myself in it, or some sort of a dog maybe. The reason why I love this symbol - or character - is because of its vessel entity; unrefined hot metal transportation. It’s a volcano. As an artist I want to be like that, to expel hot and ferocious liquid metal, somehow. This is done so well with horror cinema, as I remember that we talked about this too last time; a duality between a banal situation and a hyperbolic emotion.

H.B.B : I remember. We were talking about Lars Von Trier’s The House That Jack Built, with the crucial scene where Jack kills his two sons. You know, that scene in the hunting ground, during this picnic where he points his rifle towards his kids as a way to show them how to kill an animal. What’s beautiful with this scene is the excessive feeling of strength from Jack expressing a sense of hyperbolic anger, almost as mythology. I also love it because of the set; a hunting spot composed of printed targets, where they display a blanket for their Sunday picnic.

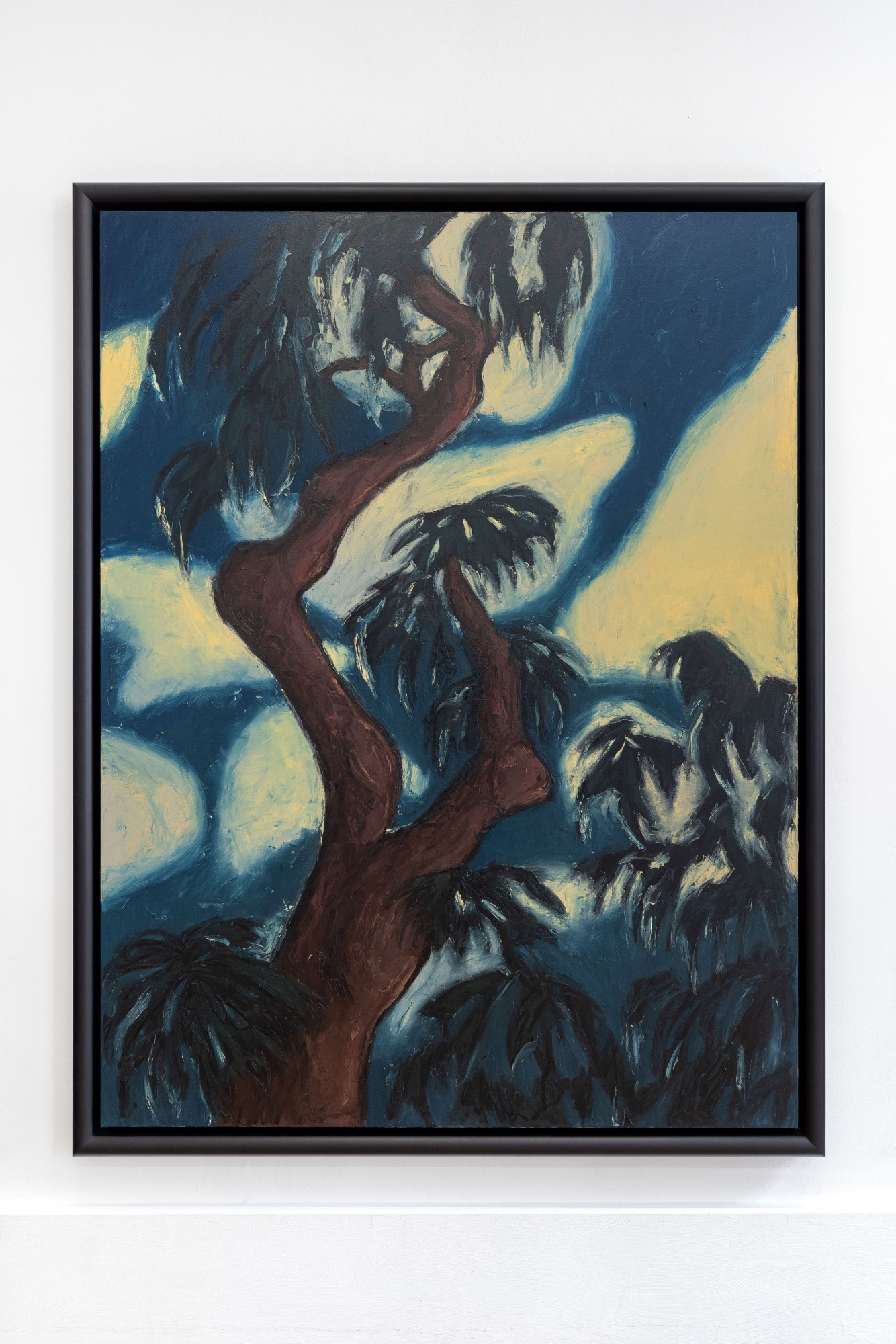

L.E : In Sturm und Drang - a German artistic movement - a broken tree is a fractured ego, a visual metaphor referring to inner habits. Those things can be evocative.

H.B.B : Especially when we think about Jack as an architect. This reminds me of Goethe’s Elective Affinities now that you mention Sturm und Drang.

L.E : But you know we’re certainly animals too. We have animalistic, irrational impulses.

H.B.B : Surely. We also talked about Soutine for a while.

L.E : Soutine is omnipresent for me, especially in the idea of a subject that remains irrelevant. Everything is imbued with those fractions we talked about; a landscape is a portrait that is also a still life. It’s never really about what is depicted but its own psychosis. The importance of the movement, too; rapid gestures, distortions, heavy shapes, and twisting forms, which draw me to a precise idea of painting. Landscapes are monsters, gremlins, devilish things.

H.B.B : I like that you speak about the devil. Somehow, your work underlines angst, which is also constant in Soutine’s work; a corpus of atrocities expressing themselves as the highest matters of the paintings. Leaving Cheyenne also refers to this attitude. Going back to this idea of tradition, I feel that your recent exhibitions interpret an idea of legacy. How would you define your relationship to this history?

L.E : It’s potentially a way to requisition archetypes while trying to find yourself within them. It’s cyclical. The human experience doesn’t change so much and the conflict is repetitive. There are certain times for attaining the future and others when it’s good to feel like you’re from the past, or everything in-between. I’m also sure these archetypes will remain.

H.B.B : Maybe more as a mythology of disaster rather than a certitude. It’s also realistic to think about the future with damaging changes. Going back to Von Trier’s movie, the final scene with Jack, when he’s in the middle of a volcano and confronted with the innermost of his core - also as a clear reference to Dante’s Inferno - shapes a sort of conversation with your recent paintings and this idea of purgatory as the basis of the work. I mean, in the movie, Jack is mostly trying to achieve a masterpiece.

L.E : That’s definitely when I started painting landscapes when I began to go inward out, as the images come from my imagination. Going into this journey is also a way of hurting myself. I can ask; what is the landscape of the psyche? Or, where is it? To me, it’s the unknown, nature, the wild, the untamed. This is also what is going inside of my mind, and body. This outward journey is also an inward one. How can you depict the human experience which is isolated in the sort of - to quote Joseph Conrad - like we live as we dream alone. It’s hard to understand other people. It’s hard to know if you’re connecting or not. How can we share our personal perceptions of existence?

H.B.B : Or as a general fear of displacement; being suddenly part of a collapse.

L.E : Totally.

H.B.B : I do feel like I enjoy what is stronger than me, paradoxically.

L.E : Also, yes. You see, the drain as a symbol speaks to that. The storm drains as places where everything is going to wind up. We’re all getting washed down and collected together with the other things, the waters of time.

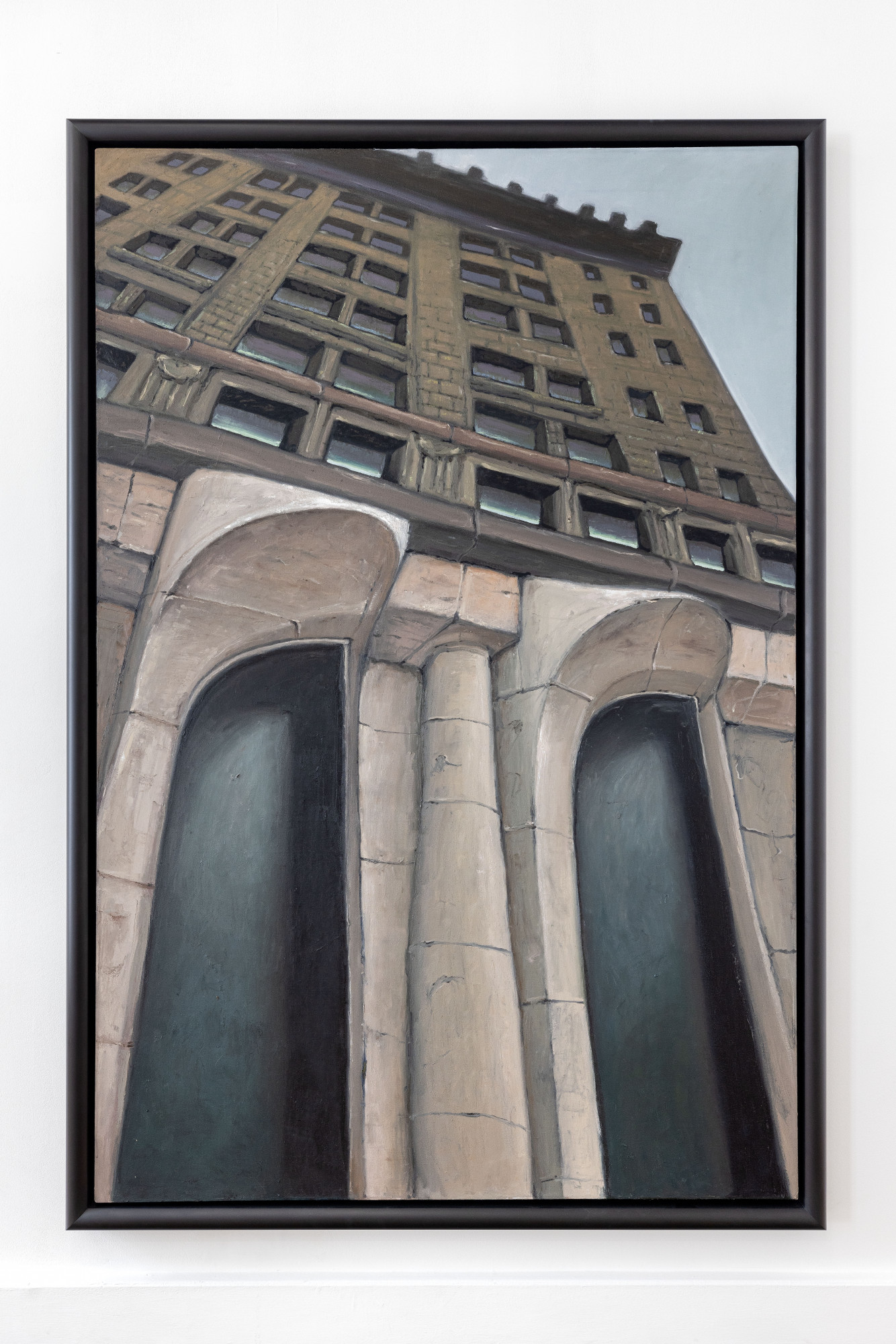

H.B.B : It’s also a matter of curiosity regarding these suspicious interfaces; the paintings displayed in the show elaborate on an ensemble of observations on buildings, windows and closed doors. It’s a corpus of observations as an interest in what is potentially happening behind.

L.E : And I think it’s scary, like living in a city and thinking about other people’s experiences. It’s frightening as it’s hard to conceive. There are so many people, and each one of them being of the utmost importance to one person, and yet completely irrelevant to the others. How we’re sharing this life with other people, and how easy it is to forget.

H.B.B : It’s probably meant to be forgotten.

L.E : Potentially too. We’re not programmed to deal with that. At least I don’t feel like I am.

H.B.B : There’s a sense of tragedy in it. I also wanted to mention Everett Spruce and the idea of failure in his Texan landscapes.

L.E : Well this is about where social realism transcended into surrealism when referring to the common every day, showing how twisted it is. The thing about the every day is that you take it for granted. You don’t think about it because it’s always there. And then these guys - Everett Spruce, Philip Evergood - would depict these things and you’re like, wait, is that what I see? You know, you’re looking at it almost for the first time. You’re looking at something for the first time that you see every day, like a landscape, clouds, or the sky. You’re like, wait, what? Oh, yeah, I totally forgot that this was there. It’s a very scary feeling. To me, it is like a horror movie to be confronted with something with your own amnesia. It also doesn’t feel like they were trying to paint well, they’re just trying to make it sensitive, to paint the feeling.

H.B.B : It’s interesting that you mention amnesia as there is a constant interest in temporality within the exhibition, a feeling of seeing something but too late.

L.E : I actually never thought about it but it makes sense, yes. I think there’s doom.

H.B.B : Revealing some sort of personal demons?

L.E : I hope so. I like to be vulnerable, both in a humorous and sentimental way, sincere sense. It’s important to show your flaws. I mean, the reason why I love Soutine or Spruce so much is because in many ways their style refers to something done so poorly. It isn’t picturesque. It isn’t something that you can teach; there’s nothing ideal. It’s fallible, vulnerable, and wrong. It’s also a need for generosity towards myself; the generosity of the expression within the paintings is a way of underlying the thickness of my sentiment.

H.B.B : What’s happening with the show, then?

L.E : Leaving Cheyenne? I think about it in different ways.

H.B.B : What about the title?

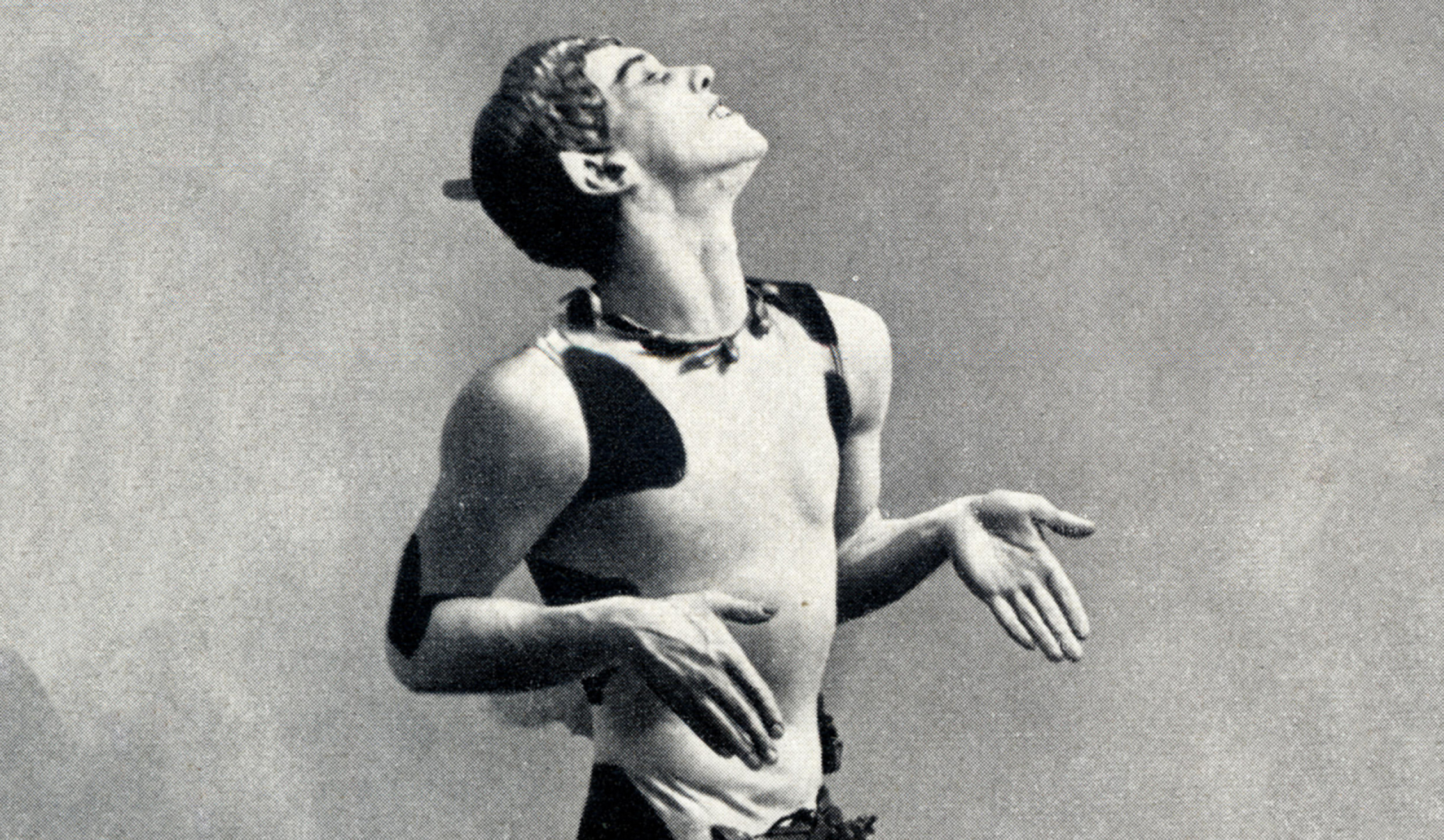

L.E : It comes from a country song reinterpreted by Arthur Russell, who was a musician from the 1980s. He was originally from Iowa but did a lot of projects in New York, and was very close to Allen Ginsberg. I like to identify with it as my mother is from Cheyenne. She left the city when her father died and moved to New York, where she met my father. I think that perhaps I, or anyone, could interpret this show as a sort of understanding of my folks and my own theogony, where I came from, the country, the land, the masculine and feminine in me. There is a sort of dichotomy that my mother met my father in New York; it’s about my own sort of nation, the places I come from. Or maybe it’s not really about that, I don’t know. I wasn’t really thinking about that when I made the paintings. I think when you have these fractured images coming from all these different places and try to put them together, or from one sentence, it’s maybe then that it opens to interpretation.

H.B.B : The sentiment of leaving a certain place is constant throughout the exhibition, certainly with a sort of melancholia too.

L.E : Totally. I think the modern narrative usually begins with an arrival and a departure. The other part of the song, which is important and I forgot to tell you about, is that the lyrics are Goodbye old paint, I’m leaving Cheyenne. Paint is a horse, here, and I like the idea of referring to something without mentioning it; a paint as a horse, or paint as just a paint; Goodbye, old paint. The rest of the lyrics are Old Paint’s a good pony, She paces when she can, Goodbye Old Paint, I’m leaving Cheyenne. So the paint is also the horse that I’m riding and that is taking me somewhere, and that

has its own autonomy. I like to believe that the paint itself is making the painting, and I’m just sort of there to let it happen.

H.B.B : The escape towards the big city is central to the work, probably as a matter of tradition too. I remember this movie by Jonas Mekas, filming a dead Allen Ginsberg in his bed in New York for several days.

L.E : Oh, yes. The Shiva.

H.B.B : It also makes sense when you talk about your mother leaving the city.

L.E : I think it was traumatizing for her to leave that place. Her father’s last words were don’t leave Wyoming, as he was intensely attached to this land, and she had to defy her father’s dying wishes to start her own life. I’m grateful she did, otherwise I wouldn’t be here.

H.B.B : Or maybe in Wyoming.

L.E : I don’t think my parents would have met there.

H.B.B : I don’t know. I often wonder if my parents could have met someone else, and imagine myself in a different context.

L.E : Well, yes, but that goes into the ideas of destiny and fate, which is something I do believe in.

H.B.B : Yes, these ideas of trajectory are prevalent in your work, no?

L.E : Certainly.

H.B.B : Something you carry behind yourself.

L.E : Trauma is certainly inherited. It makes sense. Maybe that’s where nightmares come from.

H.B.B : Probably. I love nightmares, after all.

L.E : Me too. Also, fear is primordial, and that’s why people share many of them. It’s also a survival mechanism; in order to evolve, you have to learn from past experiences, past lives, or how those things are passed on.

H.B.B : It’s interesting to speak about survival. Somehow I only read your paintings with a sense of renunciation; a lack of means to survive.

L.E : I think so too. I think that the apocalypse is a metaphor, too, for an existential crisis. That’s an interpretation, and I would describe my work as something ambiguous and hope that you could see many different things within it.

H.B.B : I agree on the hope too; ‘Leaving Cheyenne’ fatally implies going somewhere.

L.E : It’s certainly a matter of hope, like an absurd comedy too.

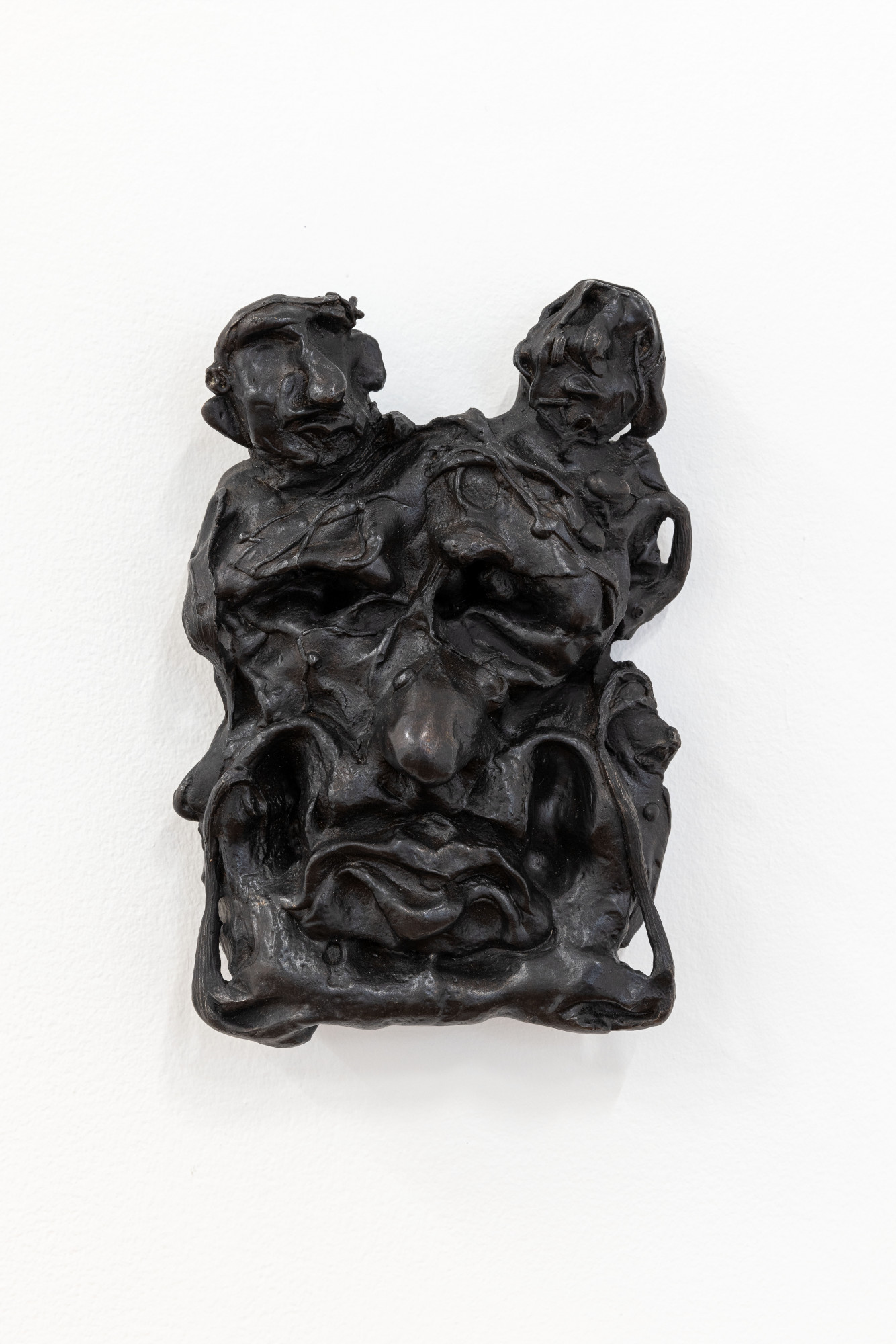

Ass Head, 2022

Bronze

33 x 7,6 x 10,2

13 x 3 x 4 in

Leaving Cheyenne, 2022

Oil on canvas

162.9 x 213.7 cm

64 1/8 x 84 1/8 in