Fitzpatrick Gallery

Paris

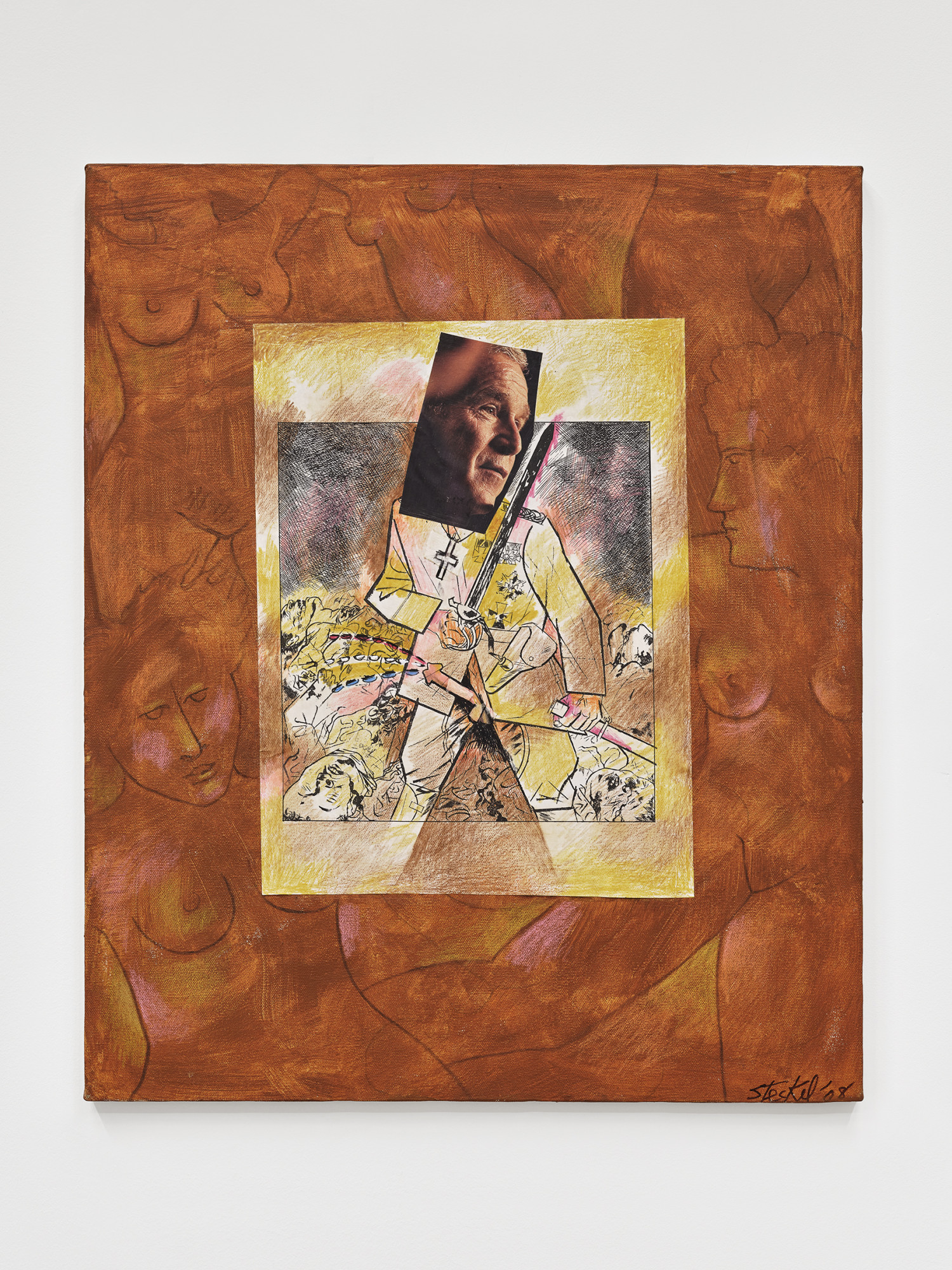

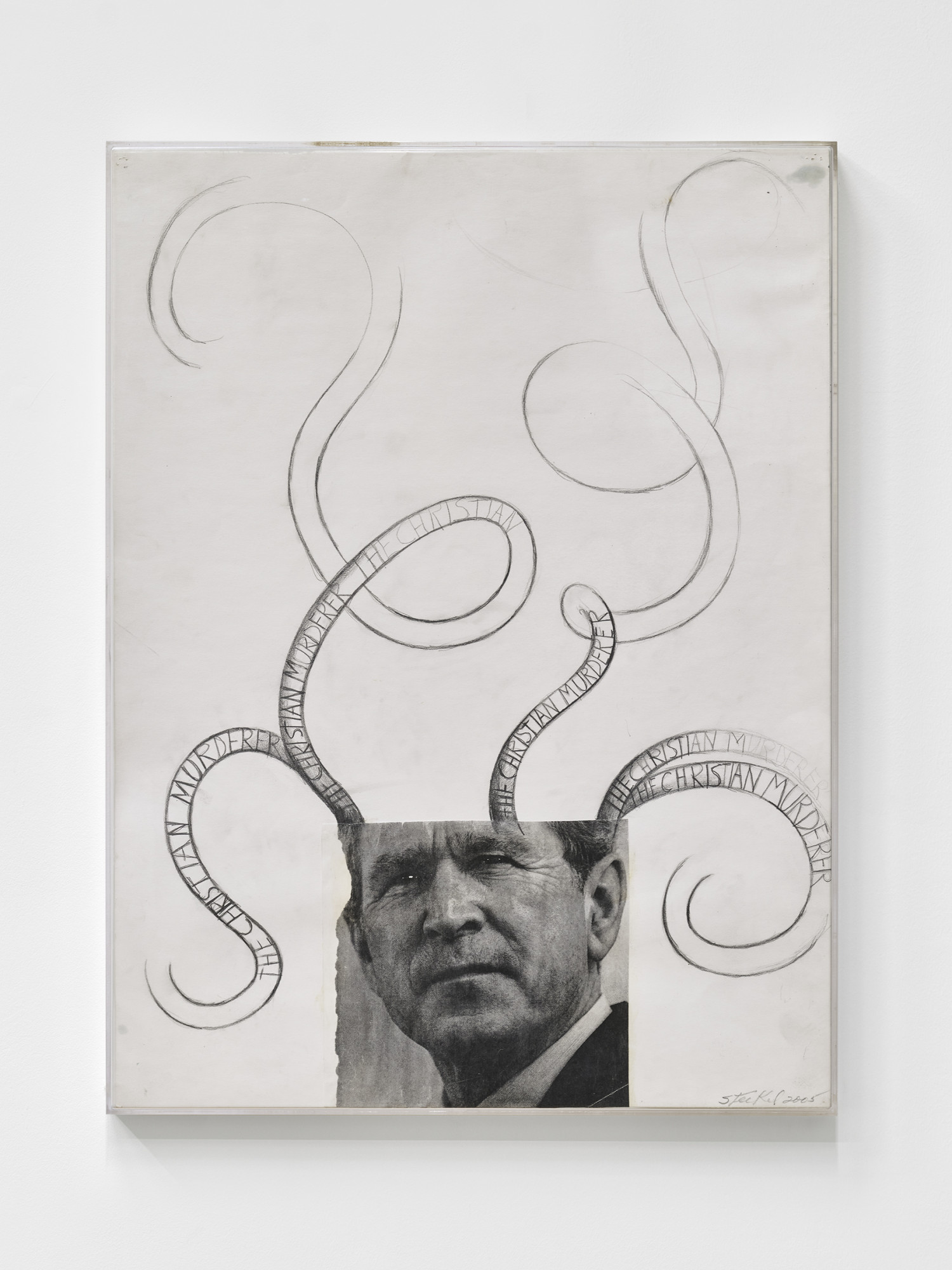

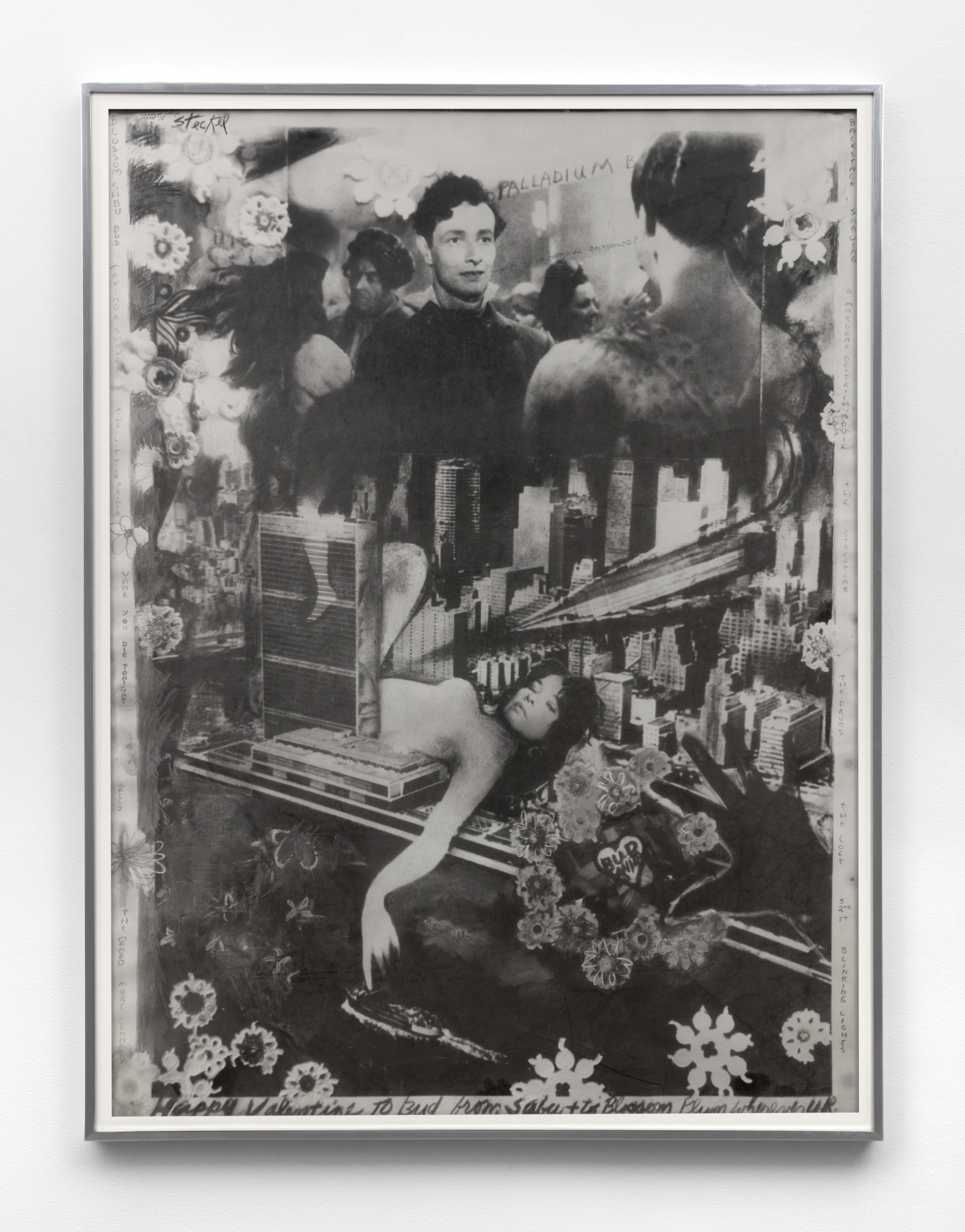

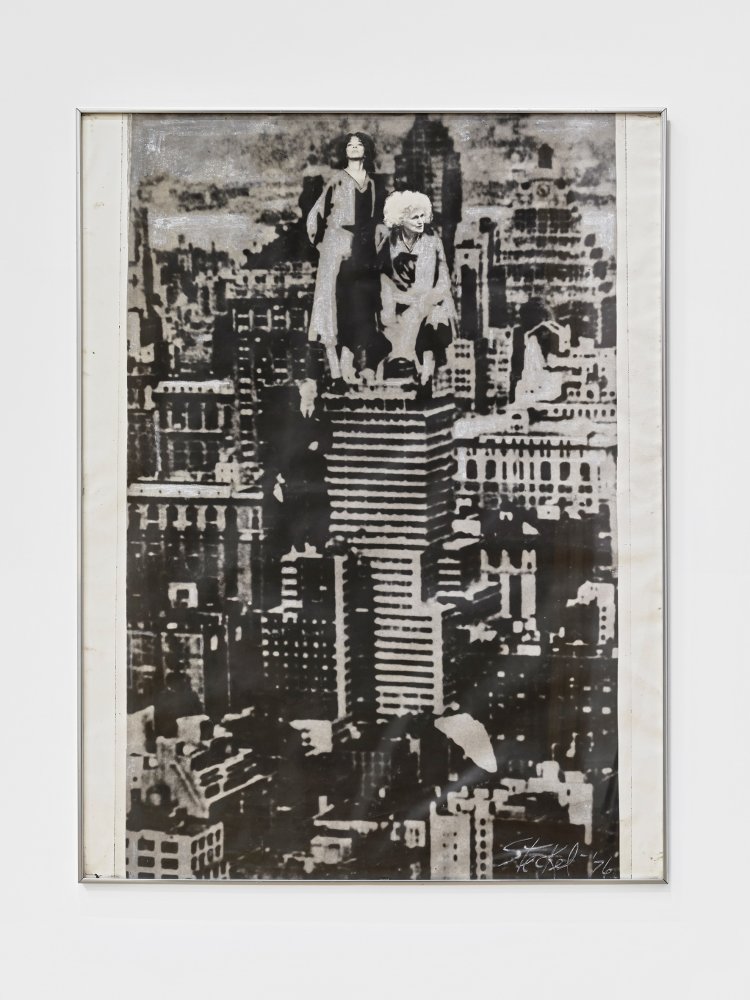

Anita Steckel

Lust

Nov 30, 2023

Jan 13, 2024

Curated by Juliette Desorgues

All images courtesy of The Estate of Anita Steckel; Ortuzar Projects, New York; Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles, and Fitzpatrick Gallery

Fitzpatrick Gallery is thrilled to present LUST, a solo exhibition of works by American feminist artist and political activist Anita Steckel. Developed from an initial presentation at Wonnerth Dejaco Gallery, Vienna (2023), these exhibitions represent the first in Europe to focus on her rich oeuvre. Curated by Juliette Desorgues, LUST is accompanied by a series of readings by French writer Constance Debré and British artist, writer and political dominatrix Reba Maybury. As suggested by its title, the exhibition induces qualities of desire and playful transgression while situating three trans-generational and interdisciplinary figures in an associative dialogue to reflect on questions of power, gender and sexuality.

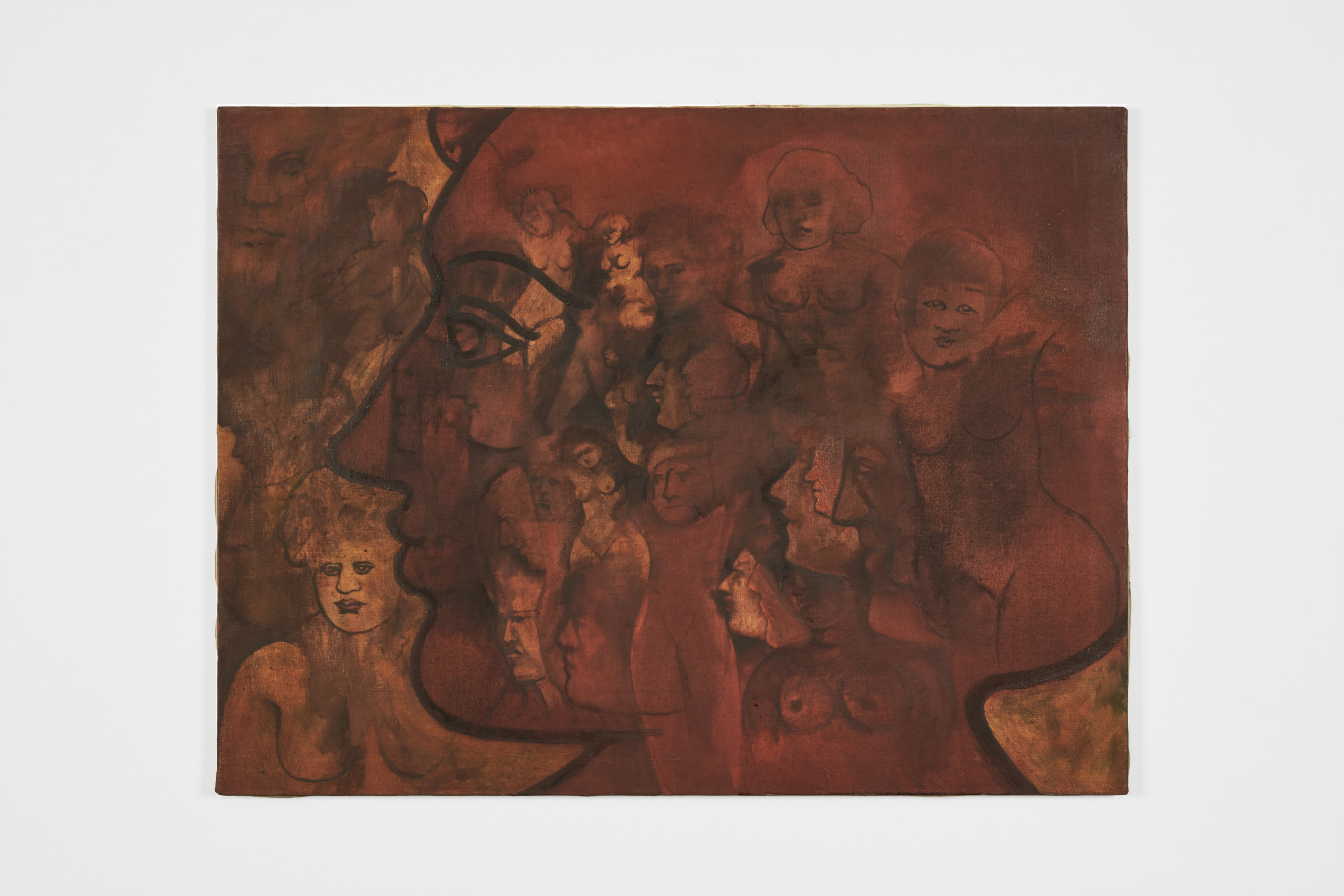

A key figure of the 1950s and 60s New York downtown scene, Anita Steckel developed a rich multimedia practice that included photography, collage, drawing and painting. Steckel’s singular body of work blossomed in the 1970s, developing in the context of the Western women’s liberation movement while challenging some of its primary assumptions. Her uncompromising work drew on sexual expression as a source for its visual content, using the space of the paper or canvas as a site for the liberation of the naked body and a challenging of the tradition of the nude at a time when pornography became a widespread phenomenon. Steckel’s employment of the naked body set herself apart from certain feminist circles, who considered such visual cues to be encased by the language of the patriarchy. It certainly provoked the conservative morals of a wider culture, which American feminist theorist Gayle Rubin describes as “treat[ing] sex with suspicion” and “constru[ing] and nudg[ing] almost any sexual practice in terms of its worst possible expression.” [1] In 1972, calls by the public and the media were indeed made to censor her exhibition at the Rockford Community College, NY due to the sexually explicit nature of some of the work on view.

Following this public scandal, Steckel co-founded the Fight Censorship collective in 1973 with fellow New York-based feminist artists Judith Bernstein, Louise Bourgeois, Joan Semmel and Hannah Wilke amongst others, who were brought together by their common practices that faced a prevailing sexist and puritanical art establishment. As outlined in the collective’s manifesto: “If the erect penis is not wholesome enough to go into museums it should not be considered wholesome enough to go into women. And if the erect penis is wholesome enough to go into women then it is more than wholesome enough to go into the greatest art museums.” [2] From this, a new form of feminist art was born, one which would be coined “sexualism”, a “phallic feminism” which denounced the instruments of patriarchal oppression while also seeing the possibility for women artists of the time to find a radical form of agency in eroticism. [3]

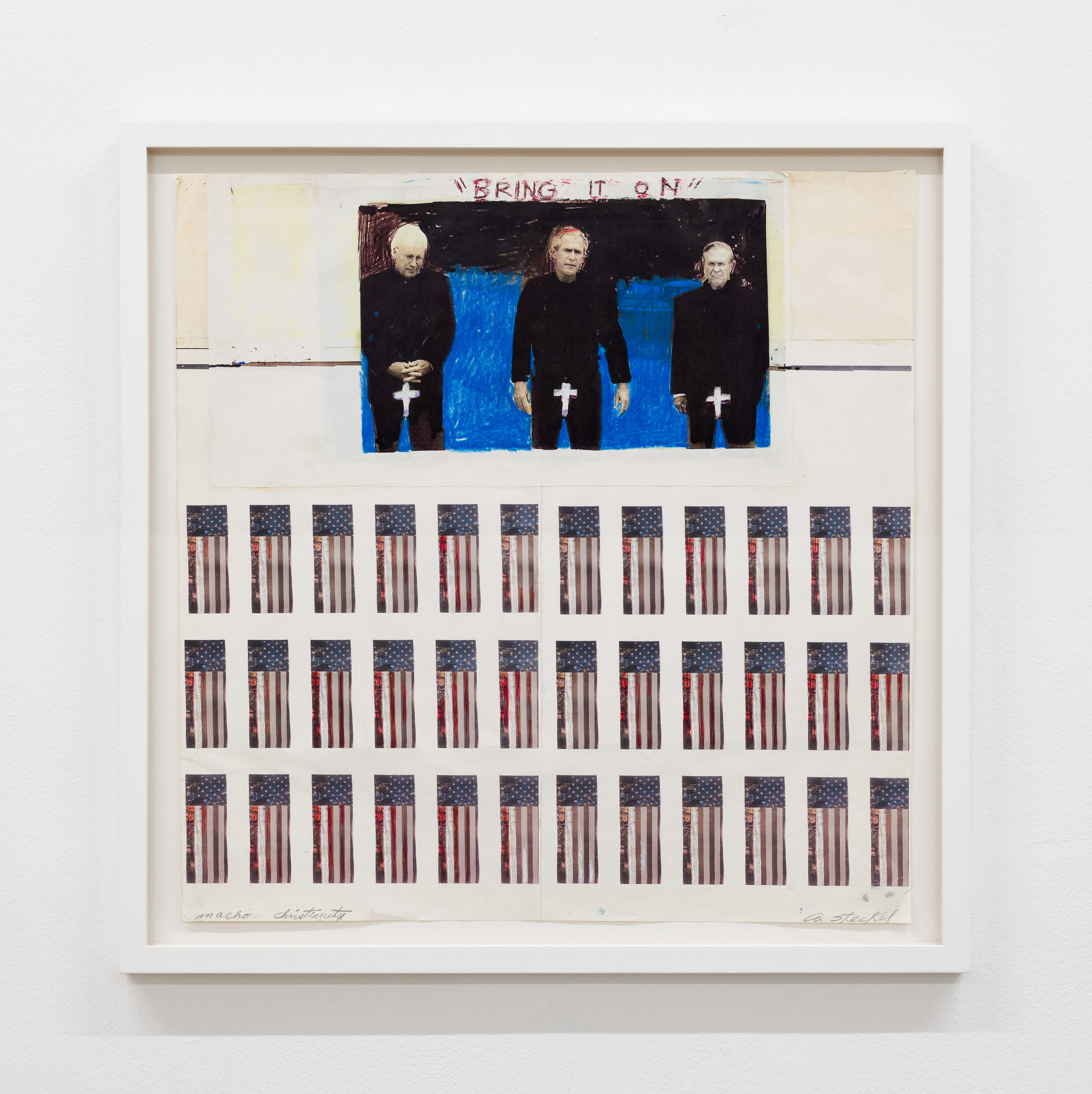

Drawn from Steckel’s archive and estate, the works presented in this exhibition span five decades from the 1960s to the 2000s. Throughout these works, phallic imagery is depicted as a cypher of systemic power, whose violent and dangerous ills are made subject to Steckel’s satirical view and critical dismantling; while the female body is positioned as an omnipotent, autonomous commander of its environment. Specific historical moments are given particular focus in this vein where visual cues to European fascism and Nazi Germany are treated with caustic sarcasm, an attitude that we might attribute to Steckel’s Jewish identity and her openly leftist politics; while the foreign policy of the second Bush administration and its involvement in the Iraq war appears as a conflation between American imperialism and phallocentrism.

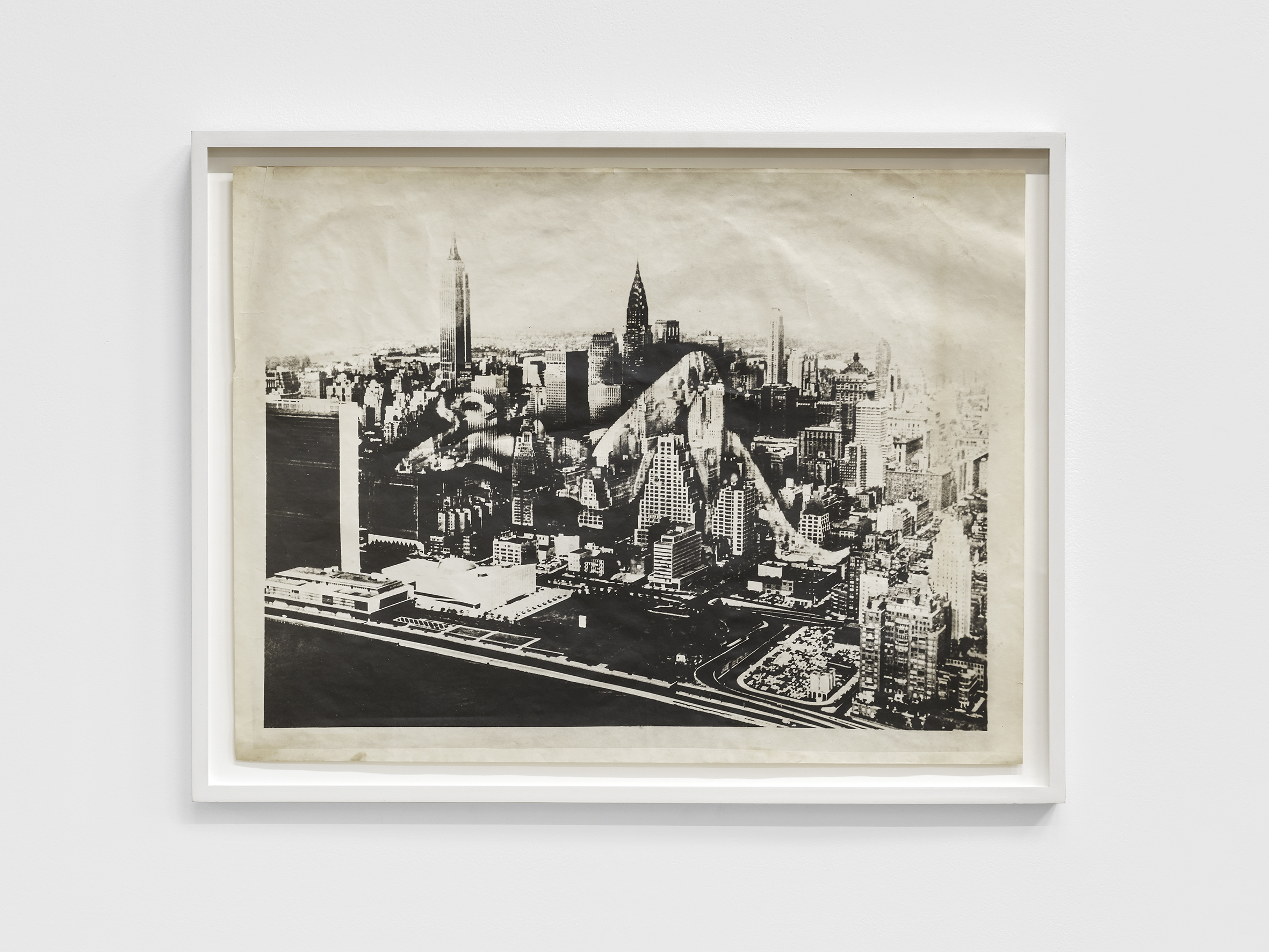

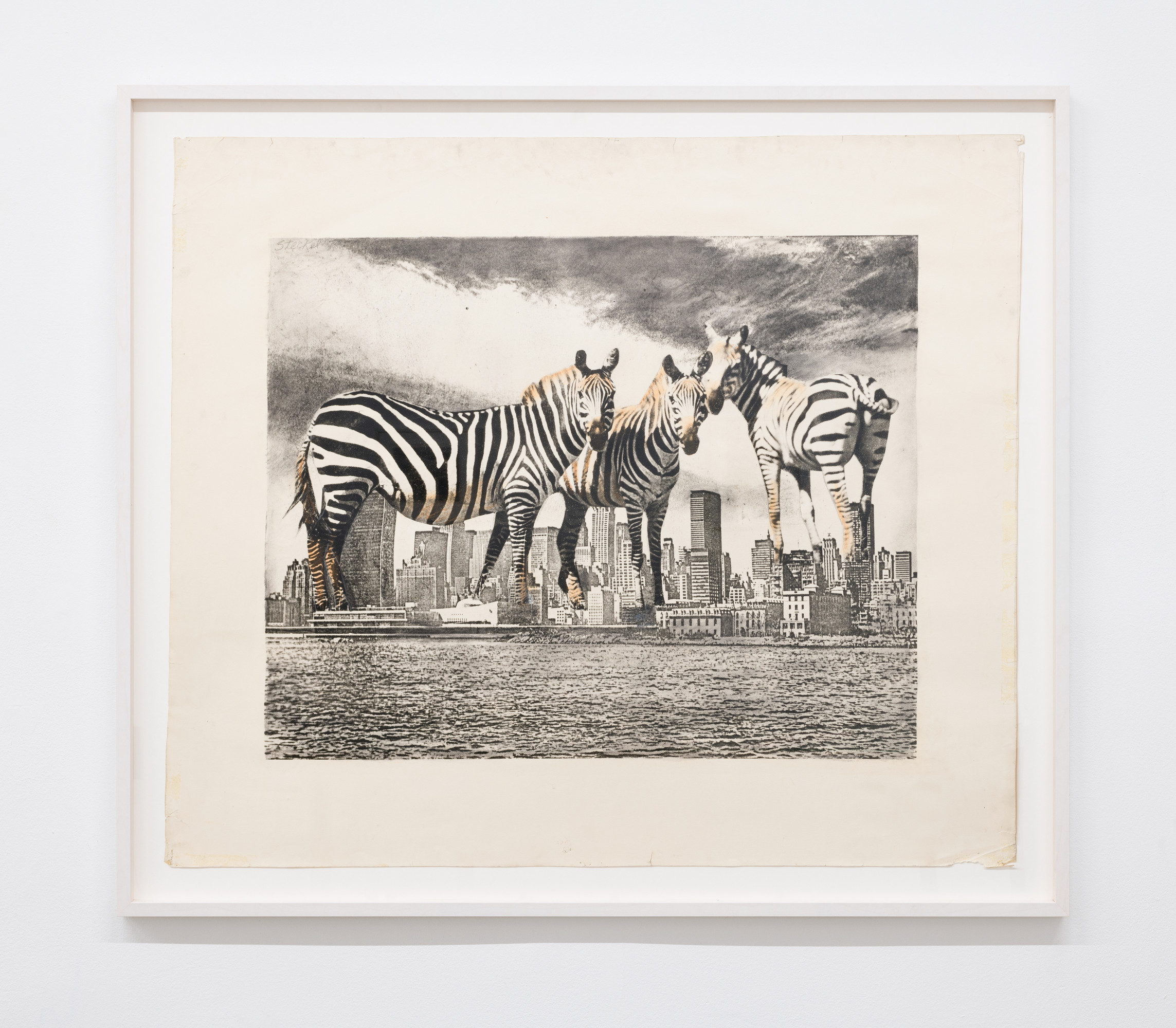

Steckel’s work suggests that the phallus can be read as a symbol of oppressive forces within the public sphere, where gender and power relations are played out and co-entwined. Steckel recurrently explores these dynamics with the imagery of urban space, for instance in the Giant Women series (1969-1974). New York City in particular is used as a backdrop against which the imposing bodies of women are deployed as signifiers of vulnerable unease. Such strategies reveal an underlying tension, one where the phallus is granted as an object of sexual desire while harbouring latent aggression. Its physical manifestation within the modern metropolis therein becoming a potential playground for emancipatory release.

On the occasion of the exhibition, Constance Debré and Reba Maybury will perform readings of new and recent texts for the opening and finissage events. While Debré’s style of writing piercingly chronicles her own personal life, her rejection of institutional bourgeois structures, and her explorations of queer sexuality; Maybury’s texts act as conceptual manifestos to her work as a political dominatrix which centres on subverting traditional gender dynamics through and within sex work.

Each of these three voices confronts the mechanisms of power, working to lay bare their structures and subverting their entrapments with humorous, raw and biting force. The self, as a lived and metaphorical entity, is deployed as a key trope to touch on wider questions of sexuality and gender, especially the role of women in contemporary society. Desire, both imagined and embodied, comes to act as a central cue, one which serves as a form of unabashed disruption to the hegemony of the normative patriarchal public sphere.

Underlying this, the exhibition asks what it means to consider the work of a second wave feminist figure such as Anita Steckel in a time of what the writer Asa Seresin calls ‘heteropessimism’, whose path is aimed toward ‘universal queerness and the abolition of gender’.[4] It is in the refusal of ambivalence as a political and embodied stance—which marks Steckel’s much overlooked life and work—that answers can be found. As with Steckel, the work of Debré and Maybury both reveal how a position may be taken, one which boldly asserts a self-determination that spits in the eye of conservative and repressive forces that continue to assert their claim on symbols and meaning.

— Juliette Desorgues

[1] Gayle Rubin ‘Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality’ in Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, ed Carole S. Vance (London: Pandora, 1992), p. 150

[2] Fight Censorship Group Manifesto “Women Artists Join to Fight to Put Sex into Museums and Get Sexism and Puritanism Out”, 1973

[3] The term ‘phallic feminism’ is cited by Richard Meyer in ‘Hard Targets: Male Bodies, Feminist Art, and the Force of Censorship in the 1970s’, WHACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. Cornelia Butler and Lisa Gabrielle Mark (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), p. 368

[4] ‘On Heteropessimism: Heterosexuality is nobody’s personal problem’, The New Inquiry, 9/10/2019, accessed https://thenewinquiry.com/ on-heteropessimism/ 28/07/2023. See also Wendy Vogel’s reading of Steckel’s work in light of today’s debates: ‘Reconsidering Anita Steckel in the Age of Heteropessimism’, Mousse Magazine, Issue 82, February 2023.

Press:

Mousse Magazine

Contemporary Art Library

The Art Newspaper

Artforum

LUST: Hugo Bausch Belbachir in conversation with Juliette Desorgues

Hugo Bausch Belbachir : The seminal 2008 retrospective at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, ‘WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution’ did not include a single work by Anita Steckel. Similarly, her work has been consistently excluded from accounts of what has been called ‘Feminist Art’, presumably because it formed an institutional critique of male domination while developing a heterosexual desire for the phallus. We know, however, that she was an active member of radical feminist groups in New York in the 1960s and ‘70s. Can you tell me about this context of representation, and how your research led you to understand Steckel as within, and at the same time outside artistic practices in the second wave of feminism in the United States?

Juliette Desorgues : One reason Anita Steckel’s work did not receive the same public reception as that of her contemporaries may be attributed to its divergence from the prevalent ideologies of the time. Despite not being featured in the ‘WACK!’ exhibition, art historian Richard Meyer addresses Steckel’s work in the exhibition catalogue. Here he recognises the limited visibility afforded to artists like Steckel, who employed phallic imagery in the 1970s, acknowledging that their art challenged the neat alignment of sexuality with political ideologies, including feminism.

Blossoming during the mid-1960s and ‘70s in New York, Steckel’s work indeed coincided with a period of significant cultural shift. The gradual relaxation of obscenity laws during this era ushered in the Golden Age of Porn, permeating both everyday culture and the arts. Notable instances include the release of the pornographic film «Deep Throat» in 1972 and Andy Warhol’s films «Blow Job» (1964) and «Blue Movie» (1971). Simultaneously, societal conservatism persisted in its apprehension toward representations of the human body. The emergence of second-wave feminism in the 1960s and ‘70s also prompted a shift amongst certain feminist artists who rejected tropes historically associated with patriarchal paradigms, in favor of more gynocentric depictions.

In this sense, Steckel’s work became marginalized for its explicit exploration of sexuality, stirring controversy both within the conservative cultural establishment and certain feminist circles of the time who viewed her use of phallic imagery and heterosexual desire as a betrayal to the feminist cause.

H.B.B: Can you tell me about the 1972 exhibition at Rockland Community College, and what led to the Fight Censorship Collective of Women Artists?

J.D : This was a key moment both in Steckel’s career as an artist and within the cultural sphere in New York at the time. Calls were made in 1972 to censor her exhibition at the Rockland Community College, due to its sexually explicit content, with legislators even claiming that the work belonged in a bathroom, instead of a gallery. Despite the backlash, and the threat of being turned down a professorship position at the college, Steckel refused to censor her show. In the aftermath of this public controversy, she gathered a group of like-minded feminist artists at her studio, including Louise Bourgeois, Judith Bernstein, Joan Semmel, Hannah Wilke, Juanita McNeeley, and Martha

Edelheit. All participants shared a common commitment to challenging puritanical and sexist artistic norms of the time, ticularly in the realm of sexual representation by women. This collective, known thereafter as the Fight Censorship Group, actively sought to promote the liberation of sexual expression in art, countering prevailing conservative trends.

H.B.B: Can you tell me about the title of this exhibition, ‘LUST’?

J.D : The term ‘LUST’ is used in both German and English to denote intense sexual desire. In the German language, it carries connotations of both desire and play; a nuanced meaning that resonates not only with Steckel’s work but also with Constance Debré and Reba Maybury’s writings, which were read as part of the exhibition. The title also finds resonance in the 1989 book «LUST» by Austrian author Elfriede Jelinek which explores power dynamics, sexuality and societal expectations within the context of a bourgeois dysfunctional family. Although lacking the playful and humorous elements present in the work of all three figures showcased in the exhibition, this book certainly provided an interesting backdrop to the Viennese iteration of the show at Wonnerth Dejaco Gallery.

H.B.B : One of the major rhetorical components of Anita Steckel’s work is her critique of the phallus. In the majority of these works, Steckel stages herself amidst New York skyscrapers, understood as phalluses in themselves, being

political, economic and cultural symbols erected as masculine conceptions. She incorporates her naked body and those of other women, rubbing up against them as players in a space that is now theirs.

J.D : Steckel’s use of phallic imagery holds a nuanced duality. In her series titled «The Grosz-est Bush: Goodbye and Good Riddance,» initially exhibited in 2008 at the Mitchell Algus Gallery in New York, the erect penis serves as a potent symbol of patriarchal violence, particularly associated with the perils of hypermasculinity, notably manifested in the context of the Iraq war. Expanding on this theme, works from the «The New York Skyline» series (1970-1980)depict skyscrapers as towering phalluses, symbolising patriarchal power that dominates the urban landscape and society as a whole. Other series such as «Giant Women» (1969-1974) from the same period turn the phallus however into an object of sexual desire and pleasure. What is particularly interesting with Steckel’s work is how it challenges traditional norms in the portrayal of sexuality. As seen in «The New York Skyline» series and the so-called Xerox prints from the 1970s, she avoids biological essentialism whereby the penis is portrayed as a disembodied, detachable cipher that can be manipulated akin to a sex toy.

H.B.B : Can you tell me more about the presence of Constance Debré and Reba Maybury within the exhibition?

J.D : I’ve always approached curating from a transhistorical standpoint; understanding historical contexts whilst reinterpreting them through a contemporary lens. When thinking about this exhibition on Steckel’s work, I found it important to extend the discourse beyond the historical narrative of her time and connect it with present-day debates.

This felt especially pertinent when considering Steckel’s identity as a white cis heterosexual woman. The inclusion of Constance Debré and Reba Maybury’s work in the show provides a contemporary context to the themes explored in Steckel’s work where power and sexuality are tackled in a similarly unapologetic way. Their contributions also serve to critically engage with the legacy of second wave feminism: whilst Debré’s writing chronicles the exploration of her queer sexuality, Maybury’s texts explore her role as a political dominatrix, focusing on subverting traditional gender power dynamics through and within sex work.